Does it seem to take a long time for your company to get a feature out the door? Have you done a “Five Whys” on the problem? Does one of the root causes seem to be the number of dependencies between teams, or “steps” that it takes to get something out the door? Chances are that it has something to do with the way your teams are structured.

The debate between feature teams and component teams is as old as Scrum is (which is getting to be Keith Richards territory). It usually boils down to:

- Component teams are more efficient because a small number of SMEs who know the code inside out are the most effective to work on that part of the code. Anyone else interfering in the code will make a mess and create technical debt.

And the discussion about possible restructuring ends there.

It ends because there is also often a hidden reason why leaders don’t want to move to feature teams. If pressed, the following concerns may emerge (if not pressed, they will stay under the radar):

- “As a leader, I am defined by the component I own, and the team(s) that work on it. I am also a SME in that component, which gives me job security. Moving to a feature team model would be threatening – Would I have a team? Would my people be scattered across multiple teams? How would i have time to attend all of those teams’ meetings? Would i still own a component?” And so on.

We will address these concerns later. But first, let’s look at a real case study…

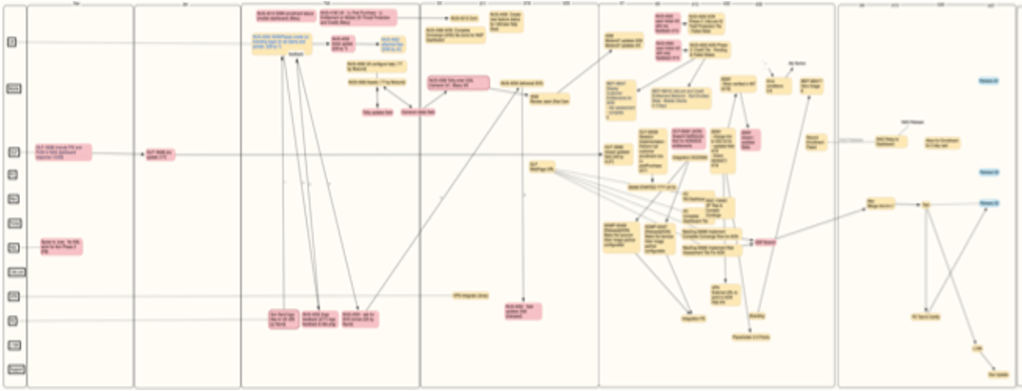

I was a transformation coach at a large software company that was struggling with exactly this issue. Minor customer requests or enhancements seemed to take forever to deliver. So I worked with a colleague to do a deep dive into the problem. We selected a simple feature enhancement that took twelve weeks to deliver once the work began and inspected every Jira ticket that related to it. The following graphic shows the dependencies between all of the teams that were involved in the solution. It is blurred intentionally of course.

Each swim lane represented a different team – front end, back end, UX, globalization, various components, etc. What was fascinating about this investigation was that the aggregate amount of time expended by all of the teams was six times what a single team could do. Not because any of the teams were inefficient – on the contrary, they worked on their tickets efficiently. But, if it only took a day or two to do their part, it basically sat in the queue waiting for the next team to pick it up. And that was where the end-to-end inefficiency was.

I used the Flow Efficiency metric to get a sense for the level of our problem. Flow Efficiency is defined as Value-added Time/Total Elapsed Time expressed as a percentage. In this case, elapsed time was 6 sprints or 12 weeks (60 working days). The aggregate value-added effort was about 60 staff-days. But this metric is usually calculated on a per team basis, which is a straightforward calculation for a single team. However, when multiple teams are contributing to the Value-added Time, Flow Efficiency would be overstated. One can divide by the number of teams, which in this case would have given us a Flow Efficiency of just 8% or so. But I think that is misleading. So we used a modified metric, which was, effectively, “How long COULD it have taken with a single cross-functional team” versus “How long did it actually take?” With that metric, the Flow Efficiency was 16%.

This data was presented to senior leadership and was considered to be very eye opening. The obvious solution would be to create cross-functional feature teams. Of course, there were concerns:

- New teams accessing code bases they would be unfamiliar with (of course, this points to deeper issues, like lack of automation and existing technical debt)

- Loss of ownership of components and people (as mentioned above)

- Some features might not lend themselves to the approach

- A general concern about disrupting the organization

To make a long story short, we took an approach that addressed all of the concerns, which consisted of these elements:

- Start small with a pilot program – we created 6 new teams, which represented only 10% of the org

- Have a change management process to onboard middle managers and team managers

- Designate SMEs on the component teams to reserve some bandwidth to help people who are new to the code base with software design decisions

- Implement a fast-feedback continuous improvement program to quickly address concerns and resolve issues

- Establish measurable metrics to represent the goals we wants to achieve, along with checks and balances

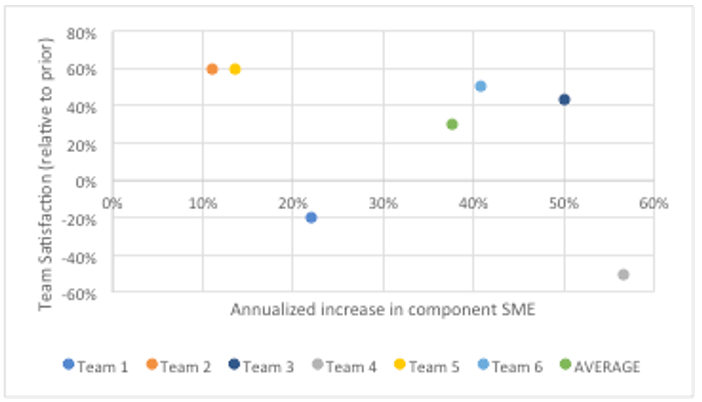

The metrics chosen were:

- Flow Efficiency, defined as described above (this is like a lagging KR in OKR parlance to measure the key objective). Because we expected some initial challenges, we also measured how fast the teams ramped up to a steady state level of flow efficiency.

- Subject Matter Expertise, to measure how quickly new developers got up to speed on unfamiliar components (leading KR)

- Team satisfaction (balancing KR)

Of course, there were bumps along the way, but by all indicators, the program was very successful and Flow Efficiency was improved by a factor of 5. Across six different initiatives, average flow efficiency for the duration of the pilot was 80%. Even better, the teams ramped up to an average flow efficiency of 89% and this was done fairly quickly – an average of 1.3 sprints, or 2-3 weeks.

Average team satisfaction increased by 30% over a period of six months, mostly because developers got out of their rut and learned new things. Subject matter expertise improved by 38% on an annualized basis.

Details of the methodology, practices, measurements, and learnings were presented in a white paper called “Winning the Concept to Cash Game with Feature Teams” at the 2021 XP Conference by Martina Ziegenfuss and myself.

Not unlike a stock investment disclaimer, actual results may vary and the variations may be substantial. But if you would like to deliver features to your customers five times faster, there is definitely value in considering an approach such as this.

I was trying too hard to do too much. Removing the impediments to a decent golf swing was far easier that trying to pile a bunch of better rules on top of the foundation of bad habits.

I was trying too hard to do too much. Removing the impediments to a decent golf swing was far easier that trying to pile a bunch of better rules on top of the foundation of bad habits.